Created by a teacher.

Based on years of educational research.

Developed by author and former teacher Jen McVeity OAM, the Seven Steps to Writing Success approach is underpinned by best-practice pedagogy that we refer to as the ‘Five Secrets’:

- Chunk large tasks: Reduce the cognitive load by breaking down complex ideas into smaller, manageable steps.

- Repetition builds muscle memory: Revisiting learnt concepts over time helps the brain retain information more effectively.

- Think first, write second: Brainstorming and planning are problem-solving activities that develop critical and creative thinking skills.

- Verbal is vital: Oral language development is one of the important precursors for success with writing.

- Consistency creates change: Regular, consistent practice develops skills, builds confidence and measures progress over time.

The principles of Science of Learning have informed the development and design of Seven Steps training and resources,

with explicit instruction core to the recommended teaching approach.

Whole school results

Since 2005, Seven Steps has helped schools unlock the inner writer in every student. Teachers from over 4,750 schools have been trained in the approach, and many have shared their inspiring stories of success:

- 35% improvement in writing data across 17 schools

- Outstanding writing success for Bunbury Primary School

- Al Sadiq College transforms their NAPLAN writing results.

In the video to the right, Mary Semaan shares her school’s results after teaching the Seven Steps for just 12 months.

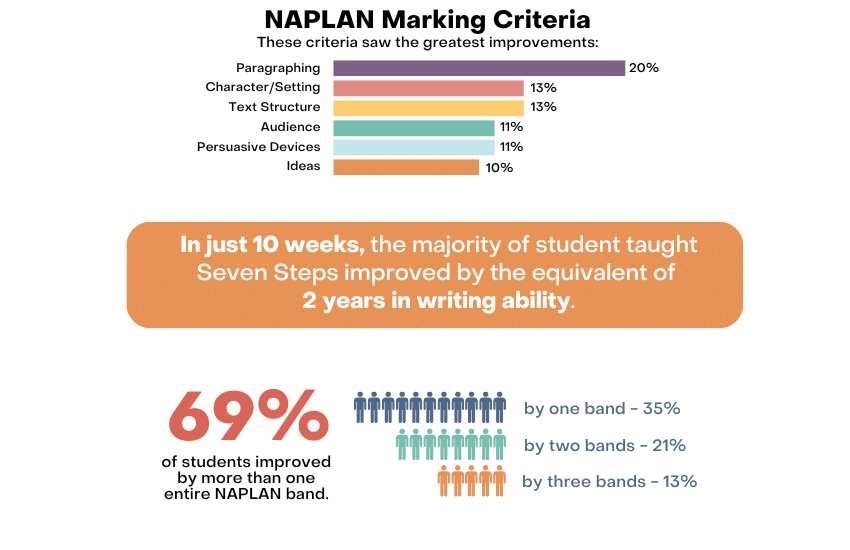

Improved outcomes in just 10 weeks

Teachers across Australia tested their students before and after 10 weeks of implementation of Seven Steps, then shared the data:

- Students’ writing scores improved overall by over 10%.

- An overwhelming 69.2% of students increased their post-test score by 1 or more NAPLAN bands.

- The greatest areas of improvement were in paragraphing, character and setting, text structure and persuasive devices.

Seven Steps Impact Report

See the impact the Seven Steps is making to student writing and engagement across Australian schools

Curriculum aligned

Our focus at Seven Steps is on the creation of great writing. Every education jurisdiction in Australia considers writing extremely important, and all educators want students to become the best communicators they can be.

Seven Steps aligns with the Australian and each state’s curriculum.

You can find matching grids and more information here: The Australian Curriculum and Seven Steps.

Step 2: Sizzling Starts is fun to teach, easy to learn and will have your students cheering for more!

FAQs

Why choose Seven Steps?

Seven Steps to Writing Success is an approach to teaching that empowers teachers to inspire their students to rapidly improve their writing skills, and most importantly, learn to love writing!

The Seven Steps can help you develop your students’ writing skills, improve results and increase confidence and enjoyment in writing.

Learn more:

What’s the best way to get started with the Seven Steps?

Teacher Hub is the perfect starting point for skyrocketing engagement and writing results!

With Teacher Hub, you will:

- win over reluctant writers

- free up time and energy

- reinvigorate your teaching, and

- fast-track writing results.

Are the Seven Steps suitable for my year level?

Seven Steps to Writing Success was designed by an author for real-life writing, and was originally aimed at adults. So the Seven Steps are practical for anyone looking to write better – whether they are four or 100!

Our training and resources are designed to enable teachers to understand the theory through rapid-fire activities and examples they can take back to their classroom the next day. We have resources that can be used with pre-writers, secondary students and all ages in between.

How do we use Seven Steps with other writing programs?

Unlike many other programs, Seven Steps focuses on the authorial, big picture skills of planning and drafting a text. We focus on the creative, fun side of writing in a structured way that teaches students critical thinking strategies about writing: what to say, how to say it, when to make certain decisions, and how to engage and hold a reader’s attention.

You can slip the short, fun Seven Steps activities into your weekly writing program, or you can use it with complementary programs that focus on other aspects of literacy, such as sentence structure, grammar and spelling.

There’s no limit to how you can fit the Seven Steps theory and lessons into everyday classes, whether you use Seven Steps as your sole writing program or it’s just one in your arsenal of writing tools.

Does Seven Steps align with the Australian or State Curriculum?

Our focus at Seven Steps is on the creation of great writing. Every education jurisdiction in Australia considers writing extremely important, and all educators want students to become the best communicators they can be.

Each state and territory expects its students to write narrative, persuasive and informative texts, to get plenty of practice, and to learn to communicate in written, verbal and visual means. The Seven Steps strongly support these aims, with a focus on students practising the component steps of writing in an accessible way – sometimes in words, sometimes in verbal and visual language.

For more about the curriculum, see the following blog posts:

Can't find what you're looking for?

Fill out our ‘Contact us’ form on our website here and one of our friendly Steven Steps team members will be in contact.

Alternatively, you can contact our office on (03) 9521 8439 or email [email protected]