No products in the cart.

15 min

Expert Insight

Sarah Bakker

Prepare your students for the NAPLAN writing task by nurturing great writers!

Read on to:

Table of contents

1. Understanding ACARA’s expectations

1.1 What’s NAPLAN all about?

1.2 The NAPLAN writing task

1.3 What’s NAPLAN looking for?

1.4 NAPLAN Narrative Writing

1.5 NAPLAN Persuasive Writing

2. Upskilling your students

2.1 NAPLAN and the Seven Steps

2.2 Focus on the structural Steps

2.3 Practise writing full texts

2.4 Simulate the test conditions

Don’t teach to the test.

Teach great writing.

Tailor-made for Seven Steps teachers

This award-winning series of resources and guides shows you how to use the core structural Steps (Steps 1, 2, 3 and 7) to help students approach the NAPLAN writing test with confidence!

NAPLAN Writing Success

Resource Packs and Video Guides

Everything you need to maximise your time and impact in the lead-up to NAPLAN.

What's included?

1.1 What’s NAPLAN all about?

There’s plenty of fear and controversy surrounding NAPLAN, but it’s essentially an attempt to determine whether Australian students are gaining the basic numeracy and literacy skills they require to function in today’s society.

Students in Years 3, 5, 7 and 9 are required to sit NAPLAN tests in four areas:

- Numeracy

- Reading

- Writing

- Language Conventions

Did you know? In 2023, the NAPLAN tests will be conducted in March rather than May, as outlined in the NAPLAN key dates table. A description of each test, including scheduling requirements, can be found on the NAPLAN website.

The results are then used to benefit students, schools and Australian education systems by:

1.2 The NAPLAN writing task

In the NAPLAN writing task, students are provided with a writing stimulus or prompt and asked to write a response in a particular genre (narrative or persuasive writing). The responses are then assessed using a set of 10 marking criteria:

- Audience

- Text structure

- Ideas

- Character and setting (for narrative texts); Persuasive devices (for persuasive texts)

- Vocabulary

- Cohesion

- Paragraphing

- Sentence structure

- Punctuation

- Spelling

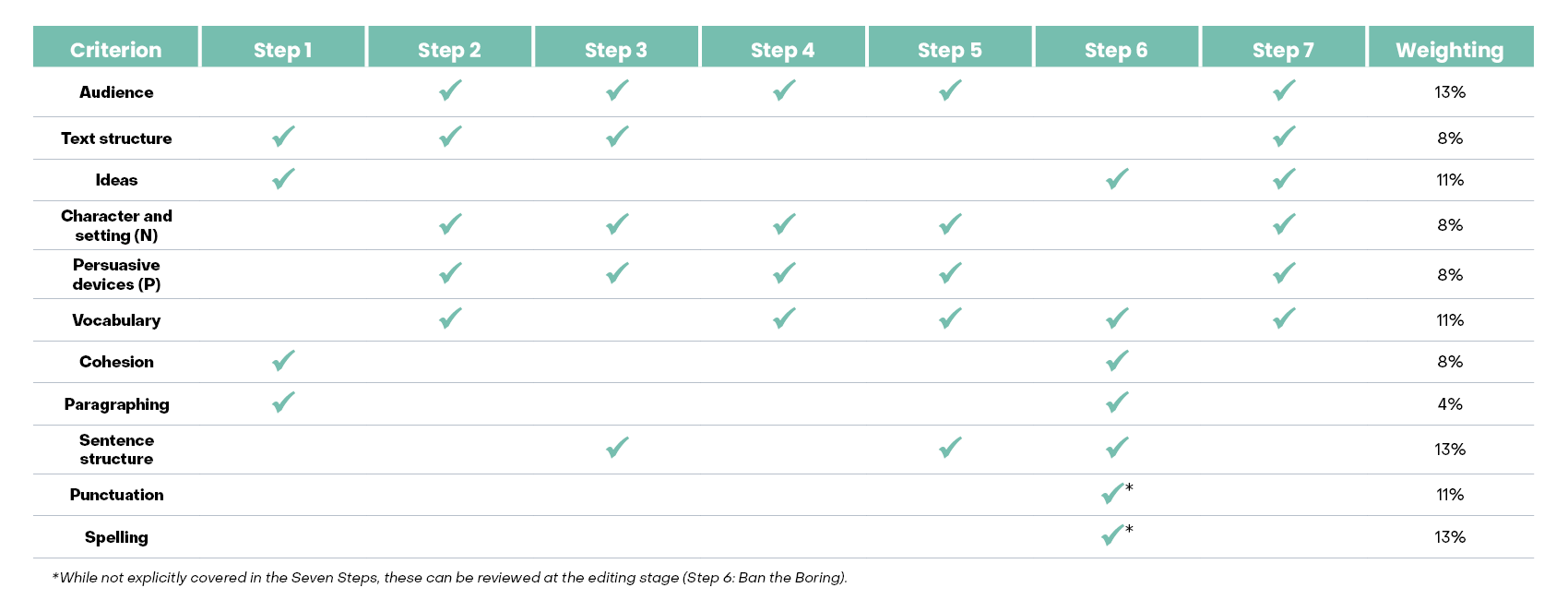

It’s worth noting that eight of these criteria focus on ‘authorial’ techniques, such as coming up with great ideas, engaging the reader, and creating a well-structured, cohesive text.

1.3 What’s NAPLAN looking for?

The weighting of the criteria is a clear indication that NAPLAN values the authorial side of writing far more than the secretarial side. With spelling and punctuation allocated just 23% of the marks available, it’s time to stop focusing so heavily on the mechanics of writing and devote more time to the critical and creative thinking skills that make writing great.

NAPLAN values creativity and the good news is that, like any skill, creative thinking can be learnt – and it can vastly improve with nurturing and practice. What’s more, enhancing students’ ability to think and write creatively not only improves their NAPLAN results but also sets them up for life as great communicators.

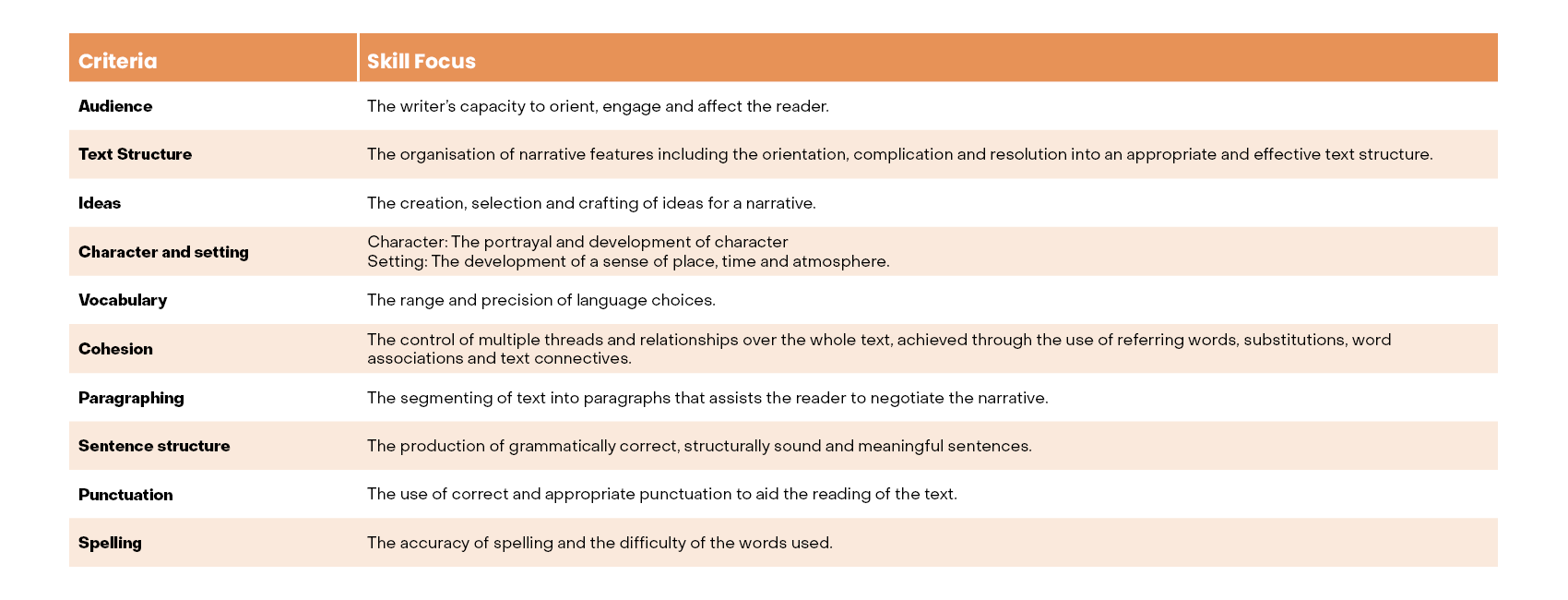

1.4 NAPLAN narrative writing

According to the Narrative Marking Guide:

A narrative is a time-ordered text that is used to narrate events and to create, entertain and emotionally move an audience. Other social purposes of narrative writing may be to inform, to persuade and to socialise. The main structural components of a narrative are the orientation, the complication and the resolution. (ACARA, 2010)

This definition has shaped the development of the criteria and skills focus being assessed in the writing task:

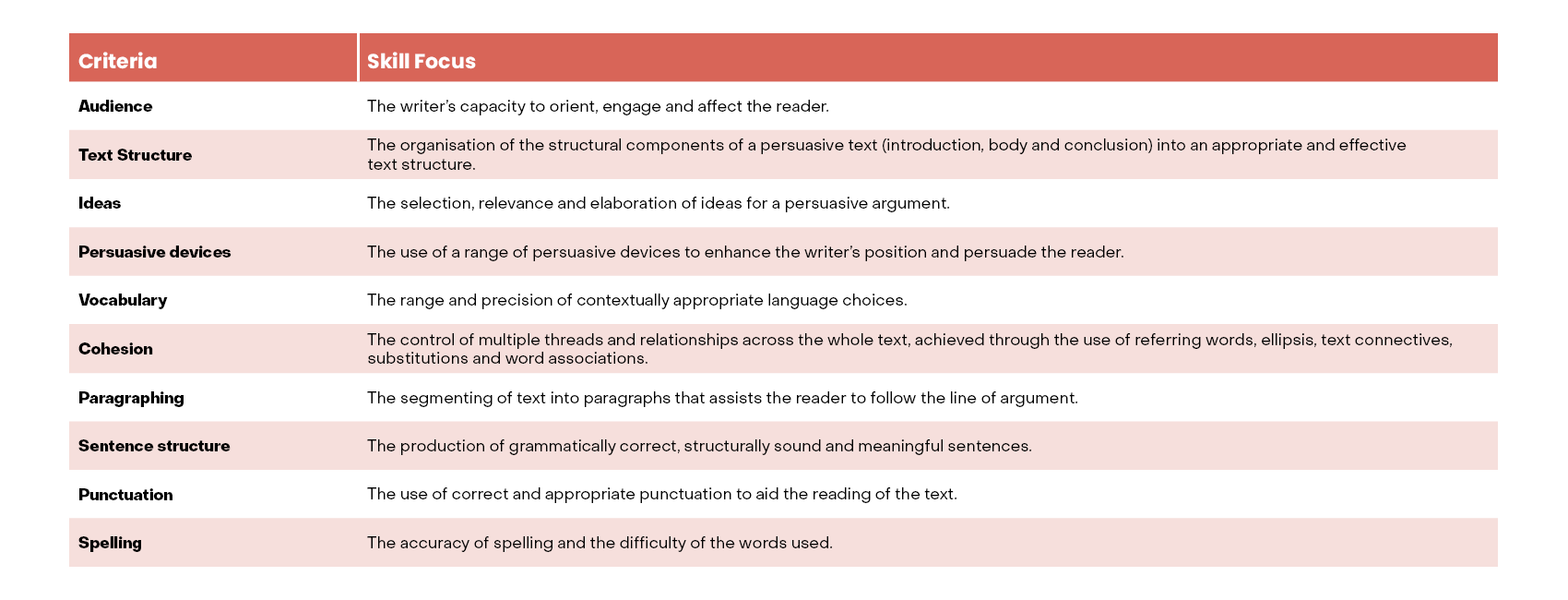

1.5 NAPLAN persuasive writing

According to the Persuasive Marking Guide:

The purpose of persuasive writing is to persuade a reader to a point of view on an issue. Persuasive writing may express an opinion, discuss, analyse and evaluate an issue. It may also entertain and inform.

The style of persuasive writing may be formal or informal, but it requires the writer to adopt a sense of authority on the subject matter and to develop the subject in an ordered, rational way. A writer of a persuasive text may draw on their own personal knowledge and experience or may draw on detailed knowledge of a particular subject or issue.

The main structural components of the persuasive text are the introduction, development of argument (body) and conclusion. (ACARA, 2013)

This definition has shaped the development of the criteria and skills focus being assessed in the writing task:

2.1 NAPLAN and the Seven Steps

The Seven Steps techniques help students to be creative, engaging and powerful, rather than just neat and grammatically correct. This means that the Seven Steps are not only great for NAPLAN prep but for improving writing in general.

Related: What are the Seven Steps?

Ideally, you would spend 10 to 16 weeks teaching students all seven Steps before they sit the NAPLAN writing test. If you’ve attended Workshop One: Seven Steps to Transform Writing, you may have done this already.

Workshop One is a great way to learn Seven Steps theory and see the techniques in action before implementing them in your classroom.

For now, let’s just focus on how you can make the biggest impact on your students’ writing. We recommend the low-hanging fruit approach, whereby you focus on the areas that will gain students the most marks.

The table below shows the weighting for each of the NAPLAN criteria (explored in sections 1.4 and 1.5) and the Steps to focus on to improve students’ results.

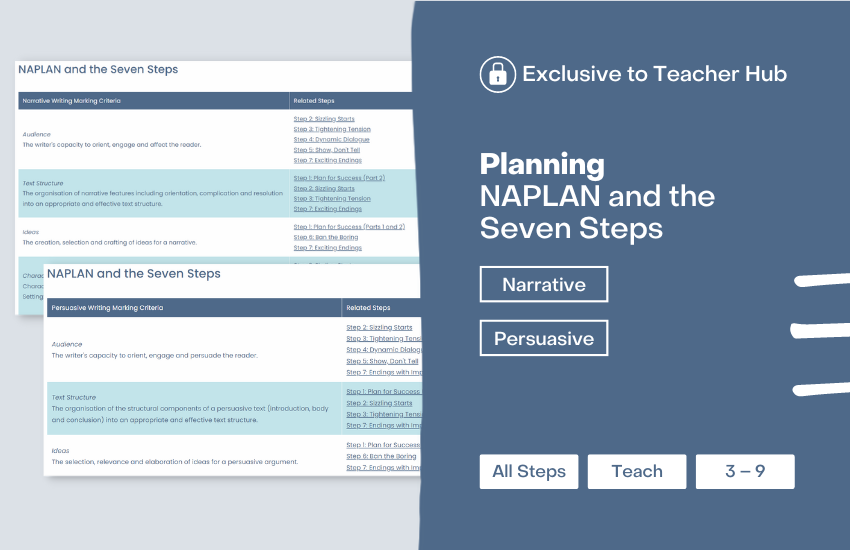

Want to find out more? Check out the following resources in Teacher Hub to find out which resources to use when focusing on particular aspects of NAPLAN:

NAPLAN and the Seven Steps

Narrative | Persuasive

2.2 Focus on the structural Steps

The structural Steps will have the greatest impact on improving students’ writing. The structural Steps are:

- Step 1: Plan for Success

- Step 2: Sizzling Starts

- Step 3: Tightening Tension

- Step 7: Exciting Endings/Endings with Impact.

These Steps help students understand the structural components of writing. In other words, they teach students how to:

- come up with original and unexpected ideas

- start their story with a bang

- build tension through a complication or complications

- craft a great ending.

As you can see from the table above, these skills will make the biggest difference to students’ writing and gain the best results in NAPLAN.

Check out these top tips and activities to get your NAPLAN preparation started.

NAPLAN Writing Success

Resource Packs and Video Guides

Practical, effective and fun resources that are ready to go in your classroom!

Tailor-made for Seven Steps teachers

This series of resources and guides shows you how to use the core structural Steps (Steps 1, 2, 3 and 7) to help students approach the NAPLAN writing test with confidence!

WINNER – Teaching or Reference Resource (Secondary) – Educational Publishing Awards Australia 2023

SHORTLISTED – Teaching or Reference Resource (Primary) – Educational Publishing Awards Australia 2023

Learn more →

2.3 Practise writing full texts

When teaching the Seven Steps, students don’t write an entire text by themselves until they’ve mastered all the Steps (or at least the structural Steps: 1, 2, 3 and 7). Asking them to do this for the first time in a test situation – in just 40 minutes! – is setting them up to fail.

Make sure that you allow time before NAPLAN to practise writing complete texts in groups and then individually, so your students will be ready by test day.

Are your students doing NAPLAN Online? Check out these tips and tricks for NAPLAN Online.

Putting It All Together modules

Exclusive to Teacher Hub

Work your way through this module to help students use all the Seven Steps techniques to create texts that captivate an audience.

Putting It All Together for NAPLAN

Exclusive to Teacher Hub Essentials

Help students pull everything they have learnt together to create an entire text. Feel free to speed up or slow down this test practice process with your students based on their ability level.

2.4 Simulate the test conditions

When preparing for NAPLAN, it’s a great idea to simulate the test conditions to ensure that students are comfortable.

Think about:

- the environment – such as the room, chairs, clock, posters on the wall and even the time of day

- the resources – such as the time available, paper, writing prompt and instructions

- the interactions – including what you can and can’t say or help students with.

Track Your Success

Exclusive to Teacher Hub

Our Track Your Success resources on Teacher Hub will help you practise for the test and identify any areas of weakness that need to be addressed in the lead-up to the big day.

View resources >

Check out the official NAPLAN documentation via the following links:

- NAP national protocol booklets

- New South Wales

- Northern Territory

- Queensland

- South Australia

- Tasmania

- Victoria

- Western Australia

- Australian Capital Territory

Looking beyond NAPLAN? If you’ve been trained in the Seven Steps and want to take your class or school to the next level, come along to Workshop Two: Putting It All Together. You’ll learn how to apply the Seven Steps at every stage of the writing process – from brainstorming and planning, to feedback and revision.

3. Reflecting after NAPLAN

Yay, you did it! NAPLAN is over for another year. Before you move on, spend a bit of time reflecting with your students on how they went.

Taking the time to reflect on the NAPLAN writing task as a class while it’s still fresh in students’ minds will further their learning well before the marks are released. It’s also a great opportunity to celebrate what everyone has achieved!

Use these discussion prompts to help students reflect on their own experiences.

Ideas

Discuss the topic that your students wrote about.

- What did you find hard about the topic?

- What ideas did you come up with?

- How did you select the best idea for your text?

Concept development

Ask students how they developed their initial idea into a complete text.

- Did you have enough time for planning?

- Did anyone visualise or sketch the story graph to help structure their ideas?

Engaging the audience

Ask a few volunteers to explain how they started their text.

- What Sizzling Starts technique did you use to engage the audience immediately?

- Did anyone use more than one technique for added impact?

Building tension

Revisit how to build tension in a narrative text (pebble, rock, boulder) and a persuasive text (strong, medium, strongest argument).

- Did anyone manage to apply these principles when writing their text?

- What other techniques did you use to build tension?

Wrapping up

Ask a few volunteers to explain how they ended their text.

- Did you plan your ending before you started writing?

- What Exciting Endings/Endings with Impact techniques did you use to conclude the text and satisfy the reader?

Adding richness

Revisit how to add richness to a text using Dynamic Dialogue and Show, Don’t Tell.

- Did anyone manage to include dialogue or a ‘show’ scene in their text?

- How did these techniques enhance the text?

Editing

Discuss the time allowed for editing.

- Did anyone have time to do a structural or an expression edit?

- What structural changes did you make and why?

- What did you change to improve the expression (sound of the text)?

- Is there anything else you would have done if you’d had more time?

NAPLAN Insights

Exclusive to Teacher Hub

Take a look at Seven Steps creator and CEO, Jen McVeity’s videos and find out what she’s learnt from sitting the NAPLAN writing task each year. Topics covered:

- Introduction: Jen sits NAPLAN

- The one thing to really work on for NAPLAN

- So, how did I plan?

- A great way to engage the audience

- The next best way to improve marks

- How to practise for NAPLAN

A handy compilation of her most valuable takeaways designed to help your students plan, write and edit a response under test conditions.

A handy compilation of her most valuable takeaways designed to help your students plan, write and edit a response under test conditions.